The Islands of Guna Yala

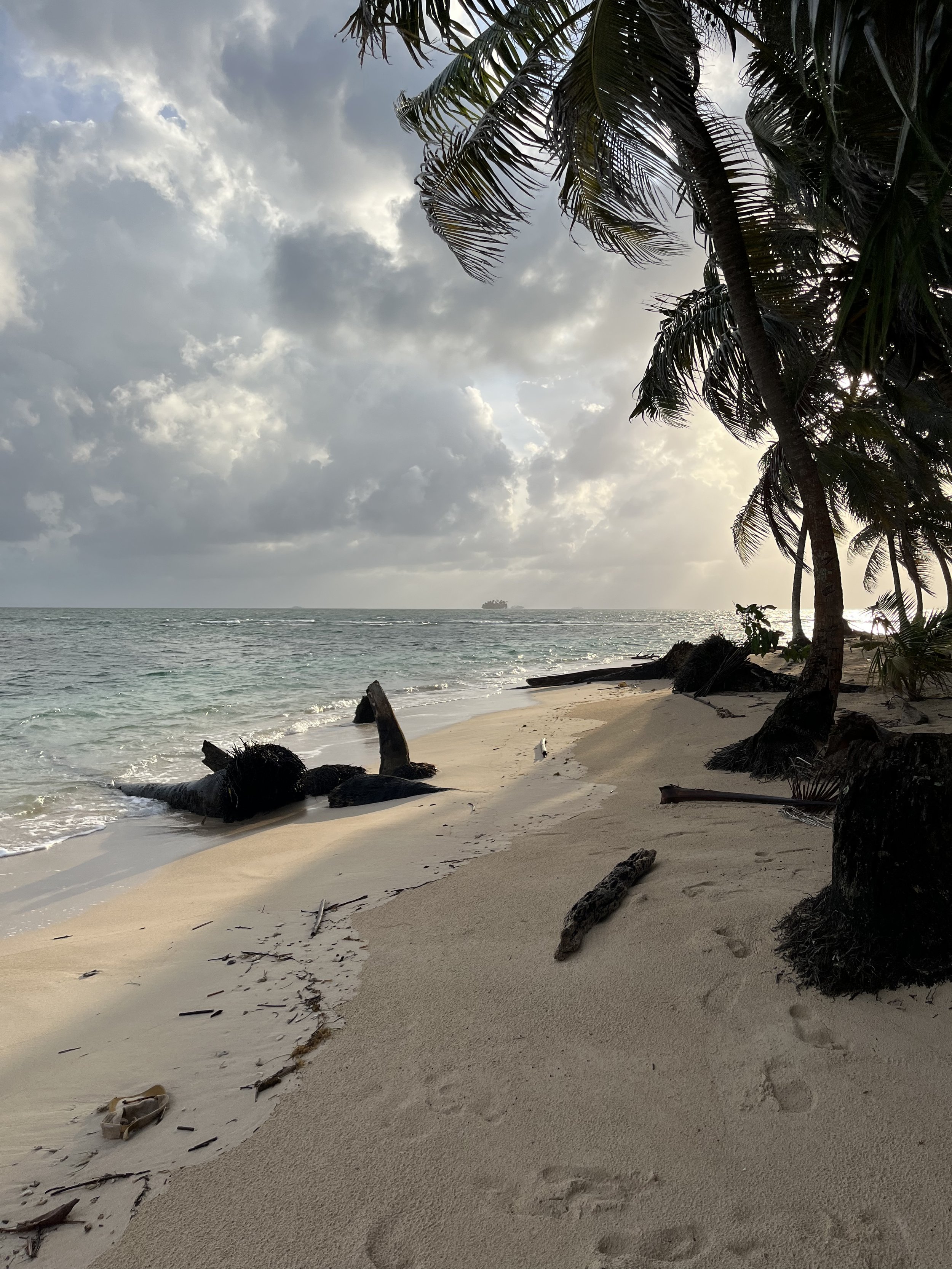

A view from the island shortly after sunrise. Jon Hull

An Aruban, Dutchman, Panamanian and I sat on a concrete dock, drinking beers, watching the moonrise over the Caribbean in Guna Yala. We reached the island earlier that day on a small speedboat. We were officially there on school business, but it didn’t feel like work.

As the moon lit the water, the four of us discussed our upbringings, shared stories from our travels, and recounted the day. We had an eventful morning and afternoon. Mark, our guide, took us all around the islands.

…

Our motorboat puttered up to the dock. Small homes with walls made from rainforest materials sat shoulder to shoulder on the shore. No land was visible aside from a sandy path leading from the dock. Waves lapped at the outer wall of each house.

A larger boat dropped anchor 100 feet off-shore.

“That’s a Columbian boat,” Mark said. “They come selling pots, pans, and other goods, and the Guna people trade coconuts as currency… the exchange rate for coconuts is one coconut to 35 cents.”

Mark leads us through the community to the school. Jon Hull

Mark unleashed one incredible fact after another as we walked onto the island. We wound our way through a series of alleys, under thatched roofs, and into the backyard of the village chief’s home. He comfortably sagged in a hammock and welcomed us to the island. His home was not discernably different from the others.

Guna Yala community islands are packed with people. The largest are hardly more than a stone’s throw across. The ocean assures that their buildings are in a constant state of accelerated entropy.

The Guna tribe makes the laws in the province, and it was evident we were among people who had intentionally separated themselves from Western influence. The group arrived here about 150 years ago. They are originally from the Darién area but moved North to escape the malarial rainforests. In 1925, the Guna people planned and executed a successful revolution against the Panamanian government to prevent “forced assimilation.”

Despite their rich history, the Gunas are still adapting to their island life. Mark noted, "Their main threat is themselves. They often remove barrier reefs for land reclamation, inadvertently endangering their own homes to wave-damage."

Trash poses another challenge. Until recently, it was perfectly fine for the people here to throw their trash out their back window into the Caribbean. Practically all of it was biodegradable. Over the past twenty years, more plastic goods have made their way here, and the islands are not equipped to handle the garbage.

“People continue to throw things into the ocean because that’s what they’re used to, and there’s no place to put it… they need the education and infrastructure to eliminate the trash problem.”

We walked through narrow dirt streets to the local school and conversed with Dalys, the school director. Having lived and taught in Panama City for 20 years, she exemplified the Gunas' dual identity of preserving tradition while embracing modernity.

The old customs are alive and well: most women are dressed head-to-toe in beautiful Mola designs; men paddle dugout canoes to the shore to get supplies from the jungle; and the entire village becomes a week-long party when any girl begins menstruation.

The latter will keep us on our toes when we set out on our field trip. We visited multiple community islands to create a backup plan in case a “period party” is raging when we arrive. That is an entirely new wrinkle in field trip planning for me.

Spearfishing in the Caribbean

It is said that there are 365 islands here (one for each day of the year). Any one of the uninhabited islands could be the setting for a “man stranded” cartoon—a spit of yellow sand with a few scraggly palm trees rising to meet the sun.

We motor through the water to our island for the night and unload the boat. Crystalline water in every direction. The palms—large and weighted with coconuts—sway overhead. The only sounds is the waves, wind, and quiet conversation.

We pull on fins, don masks, and grab a couple of Hawaiian Sling pole spears. We sit in the surf as Mark shows us how to use the rubber band to launch the spear before we go. He takes the lead, kicking out past the reef. I am ready to kill some invasive, venomous Lionfish.

It turns out I’m not a natural snorkeler. My mask fogs constantly. I choke on salt water five or ten times. Gradually, though, I get the hang of it and start diving down 20-30 feet to find our prey.

We circumnavigate the island in about 45 minutes without seeing much. Bleached coral, a turtle, and some starfish. I spear three plastic bags and a used diaper (I throw that one back).

A Second Attempt

I am back on the island after a few months away—now with students. After a long day of chaperoning, the sun hangs low in the sky. It will set in two hours.

Thirty feet below the windblown surface of the Caribbean, I come eye to eye with my prey. He is unperturbed by my presence even as I pull tension on the elastic of my pole spear. I release my grip. The spear rips through the water.

Lionfish are invasive in the Caribbean, so it is open season for freedivers with pole spears like us. We were five in total: three Guna men—locals to the area—Mark, and myself. I am the only novice among the group.

I am not a freediver, let alone a spearfisherman. As such, the blood is pounding in my ears as I approach the fish. A shadow of doubt flashes through my mind as I ready the spear. The spikes stand tall on his back, packed with enough venom to send me to the hospital.

We are past the reef in about 100 feet of water, three hours from the nearest adequately equipped medical center. I share responsibility for forty students on the island. I do not want to get stung.

He registers my presence at last and lazily drops a few feet deeper. By now, I am nearing 45 seconds below the surface, straining against the lack of oxygen and unaccostumed to the water pressure. I should surface now.

Instead, I swim deeper, take aim, and loose my spear. A miss.

My instincts scream, “UP! UP!”

I may never have another chance to spear a fish like this.

I follow as he swims deeper. I pull tension, release, and miss.

Lungs on fire, my body forces me up. My legs pump automatically but each kick of my fins feels impossible. It takes 10 seconds to burst through the surface.

Mark and the others keep their heads underwater, tracking the fish. I gasp, cough, and spit. They don’t seem to notice. That was my last deep freedive.